For most of his game-making career, Australian developer dweedes has projected an image of cheeky, punkish rebellion. His website WET GAMIN has accumulated a trove of experimental games over the last decade: short works by various freeware developers that exemplify a scribbly, DIY spirit. Now, making and selling games on Steam under his studio Nonsense Machine, dweedes finds himself in the position of stepping up his commercial and craft ambitions while trying to stay true to his anti-corporate roots.

“I’ll put out games for free because it kind of lightens the load off my head,” he tells me as we chat over Discord. “I don’t have to market it, I don’t have to invest time in it. I just want to get the idea out, and then people can play it. There’s no quality target, so it’s fun for trying new ideas and throwing whatever you want out and not thinking too hard about it.”

This light-headed mode has agreed well with dweedes, whose creative strength lies in an offbeat, anything-goes jokeyness. Among the “stupid little ideas” he’s dashed off over the years: a Justin Bieber karaoke sim; a public toilet maze of strategic bladder-relieving; and — my personal favourite — A True Western Romance, a weird mix of poetry and Wild West exploration, featuring a hilariously nonsensical conversation with a senile, potato-faced cactus. In Braid 2, his unauthorised sequel to Indie Gaming’s First Masterpiece™, the player rides a skateboard mowing down Monstars with bullets, while a very loose cover of Eminem’s Lose Yourself plays — in high likelihood, one suspects, improvised by dweedes himself.

With racing life sim Dryft City Kyngs, dweedes has tackled his most commercial project yet. Made with the help of local arts funding bodies Screen Australia and VicScreen, two newly-recruited artists, and a narrative designer, the game is set in Greater Dryft City, a near-future, fluro-coloured version of Melbourne. Locations are loosely based on real places, such as Melbourne’s many Timezone arcades, or penguin-inhabited tourist attraction Phillip Island. (Amongst VicScreen applicants, it’s generally agreed that a touch of fair-dinkum local flavour is a reliable way to catch the grant-makers’ attention.) The game’s written dialogue is peppered with old-school Aussie slang, and it’s no small pleasure — for this fellow compatriot, at least — to see idiomatic phrases like “catch you round ay” and “bitta fishin t’boot”.

At first, Dryft City Kyngs’s sprites and top-down sandbox bring to mind the 90s Grand Theft Auto games, with their snarling satire and tough-as-nails difficulty, but the game itself quickly reveals itself to be quite breezy. In contrast to Rockstar’s neoliberal hellscapes, Greater Dryft City is a veritable utopia: there are no police in sight; residents happily give you their number at first g’day; and democracy has reached such radical levels that the council will repaint the roads to whatever eyesore hue you wish within a day. Got ‘wasted’? No worries, medical bills can be placed on an infinite tab. (The welfare state is in relatively decent nick here in Australia; but jaywalkers, I must warn you — this is an exaggeration.) You play as a starry-eyed romantic who has quit their stable job, and is clocking in at a boring but undemanding internship in order to sustain their true passion, the Dryft.

The protagonist is not entirely unlike the figure of the hopeful, entrepreneurial game dev. Since the rise of the ‘indie’ as a marketing term, an image of game-making has persisted: the move from small, free productions to commercial ones as an inevitable, necessary rite of passage. The amateur (so the narrative goes) mucks around on a hobbyist scale so they can perfect their craft, increasing ambition step-by-step, all in service of eventually bunkering down, risking every sweat and teardrop to birth their “real game” — that is, one that turns a profit.

But while dweedes refers to Dryft City Kyngs as a “proper game”, his use of the phrase doesn’t imply the value judgement it often carries — for him, amateur experiments and commercial projects each have their affordances. “For free games, it’s doing whatever the hell I want with no constraints or deadlines, and it’s all fun. You can improvise as you’re making it, and you don’t need to keep super organised either,” he says. “The Nonsense Machine stuff — that’s us trying to do a good job and make business out if it, and that’s really fuckin’ hard. But on the flip side, even with just two extra people, there’s no way would Dryft City Kyngs ever look the way it’s going to look just by myself. Working with other people who are the best at what they do is also really, really cool.”

THE SOUL OF TOO BIRDS GAME, another of Nonsense Machine’s collaborative efforts, released for free, came about when dweedes was approached by local rapper Realname with an idea: a video game to tie in with the identity of his industrial hip-hop outfit, Too Birds.

I meet up with Realname for a chat at a bar in Melbourne’s inner north, intercepting him at the last minute en-route to one of his solo gigs. I ask him about his attraction to video games: “If you screen record a video game at its basic function — whether it’s Pong or a Metal Gear Solid game or Call of Duty — because it’s manufactured in a digital space, all of it is art,” he muses. “Every frame is, in a way, some rare acrylic, otherworldly. The worst games in the world just by nature look good, even when they’re jank.”

True to this sentiment, THE SOUL OF TOO BIRDS GAME makes no attempt to smooth over its gamey-ness, asking the player to wander a labyrinthine, art gallery-like structure, using green, kitchen-glove forearms to smash artworks so hard that they explode. As Too Birds’ music throbs, we ascend through the building’s multiple storeys, moving through a carpeted office, an indoor field of corn and marijuana, and eventually discovering blow-up-doll aliens who have arrived from pods sitting on the top balcony. Its crude 3D models and garish, repetitive textures somewhat recall underground FPS hit Cruelty Squad, not to mention its spirit of gleeful, opaque irony — a sensibility, Realname tells me, which grew out of how the group learned to relate to each other.

“Since the first day we met up, we took the process of making shit semi-seriously, and some of our heart was on the line,” he says. “But when it came to the delivery of it — because we’re so sarcastic with each other and we’re constantly, like, trying to pull a Bugs Bunny on one another — communicating our music to the internet, or the world, mattered so little, I guess.”

There’s a link here, too, with Realname’s scabrous gaming habits. “I’ve probably played more GTA Online in my life than any other task that I’ve done. I would go on there and troll. I would genuinely be the most toxic person I could. I’ve stopped doing it because I need to find healthier ways to express my anger.” Though Realname’s tone takes on a hint of regret, he can’t quite disguise his exhilaration. “I found a glitch — you can basically noclip into a specific area and kill whoever. I would turn this game on, and make people’s nights just worse. Like, just spread negativity for hours. People would get on and they would shit-talk me, and I would Bugs Bunny ’em, you know? Like, ‘You’ll never get me!'”

When I first heard Too Birds’ music live a few years ago — at Miscellania, Melbourne’s beloved weirdo music venue — I was struck by the complementary flows of its two MCs. Realname’s has a goading energy, a nasally twang, and jumps between dense associations in short, energetic couplets. His partner Teether’s, in contrast, sits back off the beat, with a deep, drowsy delivery that lends an impression of world-weariness. In his verse for eponymous track Too Birds, Teether paints a picture of life blurred with virtual existence:

“Sloshed cunts reverted caveman

I’m talking ooga-booga

If Tony Hawk had seen our wasteland

He’d skate it like it’s wooden

I saw the glow, I was elated

Tasted like some sugar

Hands afloat, I feel like Rayman

Leaping over skewers”

The group’s sound — which I’ve heard fellow fans compare, more than once, to influential noise rap group Death Grips — is marked by producer Mr. Society’s oddball digital effects and aggressive production. In THE SOUL OF TOO BIRDS GAME, this harshness finds itself mirrored in the artworks found scattered around its environments. Made by Realname on obsolete phone apps in a deep-fried, depraved style, they range from gross-out pics of spilled food to self-referential memes, from surreal mystery to frightening abjection.

“It’s very simulated-y looking,” Realname observes. “Images and sounds that don’t make sense are such an accurate depiction of the world we live in, in a weird way? Reality is bonkers. If you had to subject someone who hasn’t done reality yet, it would break their brains.”

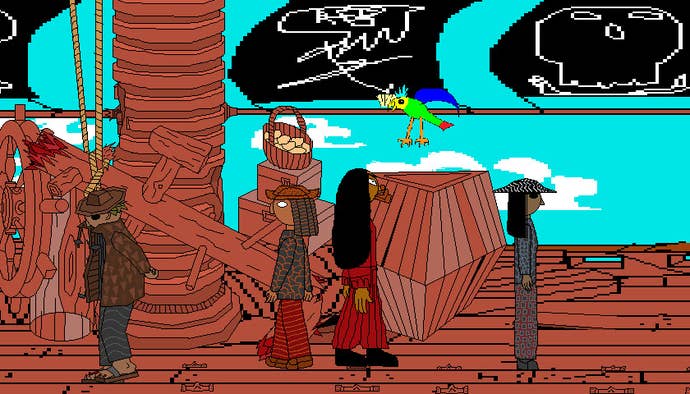

Ramshackle pirate adventure Cape Hideous, the most recent release under the Nonsense Machine label, is the work of fleet-footed stylist and experimental freeware veteran Jake Clover. You play as a pirate in a red dress and bold eyeliner, puffing three pipes as you move around the ship’s decks, windy masts, and scorching bowels via simple arrow-key controls.

After playing an in-progress version of the game towards the end of its development, dweedes suggested to Clover the idea of selling it, offering to provide original sound and music. (As a jumping off point for his games, Clover often uses short tracks from Newgrounds uploaded years before he finds them, which makes contacting the original artists difficult.) dweedes’ collar-grabbing menu track Voyage, a hypnotic, bell- and percussion-heavy tune that rings with strange harmonies, sets the mood for the brief, enigmatic journey to come.

Clover initially envisioned Cape Hideous as following in the same vein as his Dino Hunta — an outrageously puerile, slapdash experiment that might have been conceived by an unusually ambitious, war-obsessed 12-year-old boy. Over time, it morphed into something different. “At first I wanted to add speech bubbles and make a quick comedy game, then I slowly started taking more care with the animations and designs,” Clover explains. “Soon I decided to take the project a bit more seriously. It’s the longest project I’ve ever worked on.”

The game’s aesthetic bears the mark of this change in direction, and is a genuine marvel — all the more beautiful for not being so in the obvious ways. Silly, impossible sight gags — a pirate cheerfully eating a glass bottle, a large flag folded so small it can fit into a palm — mix with notes of earnest, understated wonder. While some animations are comically low-effort, others, such as the captain’s graceful movements, are impressively assured. Stuffed with ideas, liberated by a lack of concern for stylistic consistency, the art’s detail varies wildly, from naive, low-res backdrops of timber and swirly clouds, to tattered, intricately-patterned pants that look like a bathroom floor with broken tiles.

Clover elects to burrow into idiosyncratic detail, trusting that the player will notice and appreciate it. Take, for instance, the visual devotion to expressing the effects of a strong wind during Cape Hideous’s mast-climbing section, with its blowing hair, flapping clothes, and lost hats. In one miniature moment, the captain plucks a feather stuck in the wood between her fingers, and lets it fly. The ship’s inner workings and motley inhabitants follow a strange, occult logic of their own: magical tonics, spirit-bindings with sea creatures, wordless communications drawn as short reverse-shot POV inserts that give the impression of telepathic exchange.

I ask Clover about his tendency to withhold information from the player. “The sense of mystery is important to me because I want to create the sense of a bigger world through a project that’s quite small. I want my games to feel like looking through a window to a small part of a different world,” he writes. “Another idea is that I want the world to feel alien and unfamiliar, almost as if it was made for a non-existent audience, as if the game exists for reasons other than just to be played by someone.”

Clover mentions the influence of celebrated West Australian artist Shaun Tan on his drawings and storytelling, whose picture books such as The Lost Thing and The Arrival share something of Clover’s visual style as well as his sense of open-ended fantasy. Reading the introduction to his book The Bird King and Other Sketches, I’m struck by how aptly Tan’s description of his aims fits Clover’s own:

“Images are not preconceived and then drawn, they are conceived as they are drawn. Indeed, drawing is its own form of thinking, in the same way birdsong is ‘thought about’ within a bird’s throat… One of the joys of drawing is that meaning can be constantly postponed, and there is no real pressure to ‘say’ anything special when working privately in a sketchbook. Nevertheless, interesting or profound ideas can emerge of their own accord, not so much in the form of a ‘message’, but rather as a strangely articulated question.”

Amongst the Nonsense Machine slate, dweedes holds Cape Hideous in special esteem: “It’s the closest to what I would consider ‘art’ from all the games we’ve published. Thankfully looking at the reviews and responses, many people agree.” But if Clover has reached for something ‘artful’, it goes hand-in-hand with an attitude shared by its stablemates: a refusal to be clamped by the aspiring superego, and a determination to grow by no rules but one’s own.