Between fifty game releases a day, and among them official successors and open source remakes, most 90s games your grandma bangs on about have some modern equivalent that somewhat fills the gap.

But not The Settlers. There hasn’t been a Settlers game since 1996. Whether they were good or not, its many sequels, as early as 3, started missing the point of the design. It’s the roads, man. The roads!

This isn’t about iconography for its own sake. It’s a design thing, an ethos. The heart of The Settlers was that your towns lived or died based largely on how well you designed your transport logistics. It was all about the roads. It doesn’t even fit into a genre really, let alone the lopsided RTS the sequels collapsed into. It sounds like a typical town builder, especially today when there’s a wealth of games about placing a woodcutter and a farm, but I’m tempted to say it’s not even about gathering resources.

When placing buildings, resource costs aren’t even shown upfront. You’re never watching a counter tick up until you can buy a warehouse. You don’t memorise the material wealth needed to buy things: you trust that your system will provide what’s needed, and has the elasticity to adapt. Your builders set to work as soon as they have the first planks, instead of a UI nagging you “not enough rocks! (have 21 need 22)”.

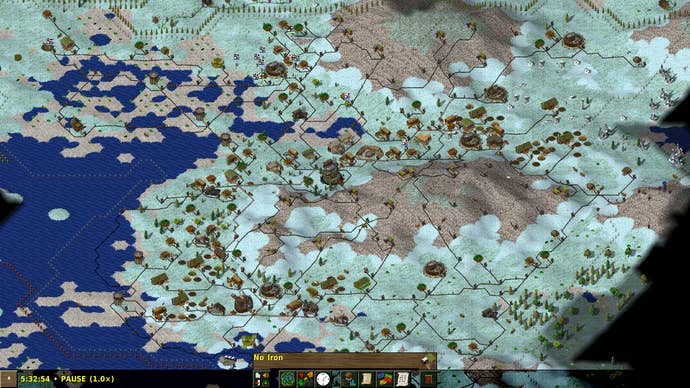

A more key part is that you build not in the centre of hexagons, but on the point where the lines around them meet. And next to each building is a little flag. You must connect that flag to another with a road, section by section, following those outlines. Goods can move only on these paths, via the noble little guys who carry them. Not assigned to the mine, or player-dictated input/outputs. One guy per road, carrying from flag to flag, always. But the direct path isn’t necessarily best. Height differences can mean steep roads, which means slow movement. They also dictate where’s where’s flat enough for larger buildings, so a longer route can be faster or leave space for a vital smelter. Soon you’ll have a network of paths and workers, all doing their best with what you’ve designed.

It’s indirect, is the thing. Connect a building site to the network and you can watch the builder walk over from the castle, a dozen carriers behind him ferrying wood and stone from a warehouse of their choosing. They might relay from the sawmill if that’s closer. Cut off a road and goods are rerouted, or carried back to storage. You’ll sit and watch sometimes, because “quickly” is a relative term in The Settlers, and because it’s delightful to watch while eating a sandwich (especially with the Amiga version’s immeasurably superior sound and music, where malnourished PC havers settled for horrible warbling synth as usual. Falsen your beliefs by denying it).

It’s also necessary. As with Ostriv (which already outdid The Settlers for watching builders work), everything you grow or make or mine or bake is a tangible item or piece or bag, visibly carried or waiting on the ground. The interdependence of production chains and slow, distributed baton-passing mean that problems start long before their effect, and you can see them coming if you watch those roads.

You don’t know that the mines stopped because of icons or blaring pop-up messages. You know because there’s nothing coming out of there, and no bread going in. The mill isn’t getting enough wheat, but you knew that because you were watching it. There’s only one road from the windmill, and it connects to your main gold thoroughfare, so the carriers are moving that first.

Meanwhile, the flourless bakery stopped burning coal, so that’s routing to storage instead, slowing movement of fish. That could cause bigger problems, but for now let’s split the road from the fisherman to let the carriers reroute. You can add near endless flags, see, and remake roads freely and instantly. Until recently I’d insist that the closest to a modern Settlers is Factorio, but here you’re reorganising things and people, not building a machine. Enabling, not micromanaging.

A good administrator knows that problems often happen far from their symptoms, and that numbers aren’t the answer. The Settlers understood that economics is not, in fact, about numbers. There are numbers and charts, sure, but you’ll seldom need them. You’re never really worrying about precision or exponential growth, not calculating success in that way. Efficiency isn’t anything that makes the number go up; it’s keeping things moving, keeping everyone supplied. Even combat means not Ctrl+1-ing a zerg of soldiers (as soon as The Settlers 3 gave you direct control of them, the series lost its way), but everyone politely waiting for their turn to fight the next guy in the barracks. Hoarding is implicitly a sign of mismanagement: That stuff should be used for something. Have I mentioned that you’re not the king here, or the mayor, or really an individual at all? There’s no currency either. Workers of the wor(“BUY WAR BONDS” – Ed)

Which brings us, with thematic leisure, to Widelands, which warns outright against such stockpiling. I’d be remiss not to mention that former Settlers lead Volker Wertich is currently part of the team developing Pioneers of Pagonia, an already promising descendant. But after a month of fighting myself to stop playing, it’s Widelands that Pagonia will have fight for the crown.

A slightly mismatched, wonky-looking game, with sometimes limited sound, it lacks some immediate charm. Many buildings look similar, and the wonderfully watchable animations that also communicated problems are now mostly workmanlike, with toggleable overlays to compensate. It’s an open-source project originating in 2002, let’s be fair. But what Widelands lacks in aesthetic polish, it compensates for with, I feel almost treacherous to say, probably a better design than the original. It is dangerously compelling.

Inspired more by The Settlers 2, it’s gone beyond both, with five distinct, quirkful “tribes” in a greatly expanded economic system. Those quirks aren’t a magic power or Special Elite Unit, either. Each side has its own building set and resources, and shared ones varying in importance. The most familiar Barbarians need heaps of wood, while the complex Frisian economy lives off their uniques: bricks, berries, barley, bees and uh, bclay. Their expansive building list takes lots of space, and more besides for the resources, sometimes an interesting challenge on the (usually playable) random maps. Amazons spurn iron altogether, making equipment from stone and quartz (from the same mine), and several special trees, whose foresters plant whatever they feel like, giving them potential to exploit useless hillsides, and a more sustainable, less mountain-dependent life. And dramatic cloaks, partly counteracting their otherwise unfortunate appearance.

None of them play wildly differently, but the nuances give each a unique economy, leaving them similar enough to be enjoyable, but different enough to provide fresh challenge and variety regardless of favourites. That extends to the military too. Combat is an often unwelcome part of building games, but Widelands takes the manufacturing focus of it even further, developing the “build armourers and smelt gold” model into a distinct economy for every tribe.

Weapons and armour must now go to a barracks to produce soldiers, who only improve by training at dedicated buildings, burning advanced weapons and armour in the process. Everyone’s details vary. Frisians can recycle some of the metals. Barbarians only need axes to start. Amazons don’t need iron at all. Combat itself lacks a little drama, but warmongers will appreciate the option to destroy instead of capturing outposts, and that wounded attackers will retreat. Each tribe’s soldiers have a different strong suit, and even guardposts vary in manpower, cost, vision and conquest range, with the Atlanteans needing three resources for a basic hut, while Amazons can post sentries in a treehouse, and get rope and tree back if they take it down again. It remains, though, a question of logistics, not manoeuvres, unit types, or specific violence.

Even pacifists need not scorn military production, since that’s a measure of victory in the “collectors” game mode, that one exception to the “hoarding is bad” principle. Buildings are never made obsolete, but deconstruction returns some resources, so there’s value in tearing down and redesigning areas over time. You can even send ships to found second towns, and split your road network into independent parts, although you’d need to plan well to achieve much.

It’s not machine building though, thanks to those little people wandering around, the irregularities of terrain and hexidirectional roads (originally a solution to programming limitations – another case of limits making a work great), and emphasis on working with the terrain. Its detail may sound exhausting, and even to a Settleteran there are new things to learn. But the underlying processes of Widelands retain that sense of reason, of problems having a traceable cause and natural solutions. And though a bit faster, it’s still very much about taking your time, looking ahead, and enabling rather than dominating your people. About keeping things moving by determining what paths they can take, not by giving orders, cold calculations or minmaxing.

I doubted there’d ever be a game to match The Settlers, since everyone who tried seems to miss why it worked. I have some complaints about redistributing soldiers, control of individual workshops, and the AI’s seemingly random switching of alliances, but those are petty, petty gripes. Widelands absolutely gets it, in a way almost the entire industry seemed to miss for decades.