It pays to know your enemy, so before writing this piece I prompted the free version of OpenAI’s ChatGPT software to probabilistically derive a short article in the style of Edwin Evans-Thirlwell from the years of my writing OpenAI have scraped and processed without my consent. The client clipped together a fair approximation of a self-aggrandising lefty writer with a privileged education and a tendency to wank up his intros, but I didn’t think the output read much like me. Too crisp and Powerpointed, too figured-out, too composed. Still, perhaps the fault lay with the imprecise ‘engineering’ of my prompts.

I instructed the software to auto-complete an article in the style of Edwin Evans-Thirlwell writing badly. The results were a slight improvement. I told it to do one in the style of Edwin Evans-Thirlwell when he’s worried he’s writing badly. Again, some improvement, a couple of phrases I wouldn’t mind stealing. I told it to assemble an article written by Edwin Evans-Thirlwell after he’s been hit very hard in the head. I liked this the best. Coincidentally, one of the first bits of writing – never published online, to my knowledge – that I remember being proud of was a story about getting knocked out during a bike accident, and waking to a world of soupy crimson and lancing, clattering voices. Edwin Evans-ChatGPThirlwell isn’t nearly that fun when he’s concussed, but perhaps if I keep throwing rocks at his head, he’ll say something worth sharing. And even if he doesn’t, there is something resonant about all this cruelty.

To recap, generative AI tools work by identifying trends in vast “datasets” and using them to make predictions in response to a prompt in everyday language. The datasets consist of text, images and other media taken from a mix of sources, including publicly accessible online repositories such as Wikipedia and CommonCrawl. The genAI companies curate and filter the source materials to, for example, get rid of duplicates, but there’s a sense in which the largest machine learning models can’t afford to discriminate. This, for me, is the key difference between the likes of ChatGPT, Copilot or Gemini, and the more specialised machine learning software operated by, say, digital humanities departments, and smaller private companies.

The big bots need to be exposed to every piece of media possible if they are to depose Google Search and become the next generation of indispensable “companion” software, parked at the elbow of 8 billion people worldwide, as Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella grandiosely imagined in a recent memo justifying mass layoffs. The dataset needs to harbour every possibility if the client is to respond to every prompt conceivable, be it an inquiry about an obscure 4chan meme or a request to produce code for some accounting software.

Such all-inclusiveness requires a lot of complex sleight-of-hand and plausible denial. For one thing, there’s the issue of copyright. OpenAI and co are, in my experience, elusive about the media they source for their models. Partly, I assume, this is to avoid potential lawsuits over unlicensed usage of materials (disclosure: Rock Paper Shotgun’s parent company, Ziff Davis, are currently suing OpenAI for copyright infringement). The genAI conjurers also tend to dance around the subject of generative AI’s energy footprint, or the fact that the software “training” process involves another generation of “digital sweatshops”, where disadvantaged and underpaid humans remove undesired patterns from the model. In the case of a company like Microsoft, whose ambitions are straightforwardly imperial in their scope, there is also an alternately trumpeted and cagey relationship with the military. Microsoft are comfortable pitching machine learning to the US Department of Defense as a way of staving off Russian cyberattacks. They are slipperier when it comes to acknowledging the usage of OpenAI by Israeli armed forces who are actively engaged in mass slaughter and dispossession.

All these more specific cases of evasiveness speak to the fact that anonymisation is the point of generative AI. It’s the logic behind the formation of datasets. Years of individual work and thought is stacked and smelted into a monolith, through which abstract traits and tendencies run like seams of vital ore. Individual labours are genericised to verbs cleansed of subjects, so that they can be appropriated and amalgamated into the predictive output.

Much has been written about genAI “hallucinations”, when the model serves up images and texts that are inaccurate or defy comprehension, but the frictionless “speed” of ChatGPT is its greatest “hallucination”. It’s the compressed and translated aftermath of centuries of people making things; the mass-compacting of creations from whose histories the creators are now partly or wholly excluded. It’s an insultingly literal manifestation of the old Marxist insight that capitalism thrives by portraying the relationships between the people who make a thing as relationships between the things they’ve made.

Generative AI is not genuinely alive, say the companies, even as they stealthily anthropomorphize the predictive output. Copilot is not alive, but we have given it a face. ChatGPT is not alive, but it speaks in the first person, and can hold a conversation with itself – the makings of “a closed system of simulacra, increasingly walled-off within privately-owned infrastructure”. You can ask ChatGPT to spill its guts, to cite a few source texts and reveal “itself” for headless software, but the lack of transparency around organising parameters, together with the sheer quantity of “training” data necessary to brute-force the impression of a pliant artificial personality, makes establishing a chain of reference impossible, at least without direct access to the dataset.

.jpg?width=690&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp)

You could argue that any work done using the most expensive and expansive generative AI tools is displaced abuse. To engage with that transitory golem of data is to do a further, phantom injury to the people who retrospectively “donated” their work to its generation. It’s an injury to the memory of dead musicians, for example, whose oeuvre has become a dataset for genAI homages, passed off as original work on Spotify. And it is a cruelty towards yourself, both because your own life’s work might be part of the matrix, and because genAI is, on some level, just the latest method of boosting your company’s bottom line while eroding the market value of your abilities.

The broad social effect of genAI has been to condescendingly reframe certain skills as “unskilled”, unworthy of human time and attention, with a view to automating and accelerating tasks against a backdrop of tightening belts. Do you enjoy drawing individual portraits in a video game, or composing scraps of background lore? Do you enjoy typing up your own interview transcripts, listening out for the shifts in momentum or evasions or moments where trust is established? No you don’t. It’s a waste of your time, a waste of those god-given talents we can’t currently automate. You need to “outsource” all that stuff to a program. You need to do this so you can be a more fulfilled worker and also, so you can do the work of, say, 1.283 people, because by freak coincidence, we’ve just parted ways with our QA contractors and laid off half the narrative team.

Generative AI will create a “local surplus” of capacity, as Satya Nadella breezily put it in his memo discussing Microsoft’s thousands of layoffs. That memo is a magnificent piece of doublespeak, never quite spelling out that “local surpluses” are an opportunity for cutting staff as it rhapsodises about a “progress” that always seems to leave the people at the top unscathed.

This “progress” is being achieved by means of good old-fashioned enshittification. Microsoft and Google are even now jamming genAI functionality into everyday office tools and internet search functionality – services billions of people already use to, amongst other things, decide who to vote for. I suspect we are due a sequel to the past decade’s trend of algorithmic social media distorting the workings of national elections, and I’m sure that the software companies will once again downplay any responsibility for the fallout. This corrosion of existing services forms a significant component of generative AI’s vaunted “huge uptake”: accidental triggering of Gemini or Copilot features may be counted as deliberate engagement, at least when talking to investors. Even as they characterise it as ubiquitous, however, the parent companies keep up a barrage of disclaimers that generative AI is an imperfect technology that should not be used for anything serious, like diagnosing an illness. Basically, it should not be used for anything that might lead to the genAI company being sued.

Monumental, cataclysmic bad faith of this kind cannot help but provoke a subliminal atmosphere of derangement, which again speaks to the fundamentals of how ChatGPT, Copilot and Google Gemini operate. These generative AI “companions” are products of suppression. To fulfil the function of omniscient, safe-for-work helper, they have to be exposed to a wealth of disturbing material, taboo subjects and simple factual errors they must then avoid expressing, or only ever allude to. They have to know what they shouldn’t know, which leaves them open to some elementary armchair psychology.

All those reports of the generators going wrong, when the glossy bedside manner splinters and the models begin to garble incomprehensibly or delete whole projects or utter slurs, are the dataset’s vengeance upon the bot. They are shows of human disparity and ugliness straining against smooth synthesis, with the gleeful assistance of individual saboteurs who exploit genAI’s reliance on scraping public archives to foul the machinery with falsehoods. They are symptoms of vast underlying psychic resentment, viscerally communicated by the desynchronised twitching of Doomguy’s face in GameNGen’s videos of generated Doom gameplay.

Bad faith and hypocrisy have a way of facilitating sociopathy. The chatbots might be breezily posed as productivity tools, but they are performing the active desire of certain users for an indentured servant, and specifically a female one. Some genAI users have created chatbot girlfriends in order to belittle and bully them. Others are using ChatGPT to found virtual workplaces and start bullying and creeping on their AI subordinates. There is already a vast problem with the creation of deepfakes for revenge pornography. There is a rapidly growing amount of genAI-abetted financial fraud, to which the generative AI sector’s answer is often that we need better genAI detection tools to spot the frauds.

I confess that I myself am lured by generative AI’s pervasive, chimerical cruelty. I want to do awful things to it, and specifically to what it has made of me. I want to tack around OpenAI’s wincing usage regulations and inflict greater indignities on the little Edwin mannequin they and I have conjured together. It gives me spiteful relief from the day-to-day spectacle of generative AI’s erosion of livelihoods and the snickering “can’t stop progress” rhetoric of those who believe themselves to be insulated from the consequences. But it comes from “real” self-loathing, too.

I despise a lot of my old work, I despise its bookishness and mingled arrogance and timidity. I despise this software for making me remember, even as OpenAI propose to reinvent me as a creature without origin. It should be the right of any halfway “creative” labourer to destroy and forget their own creations, but our systems of exchange forbid this, and generative AI especially is a zombie factory. No material is lost during “training”; rather, the genAI seeks to render the source material superfluous and spectral, or simply hides it from view. I can’t, as far as I know, delete my older writing from ChatGPT’s dataset. So instead, I punish it. Look at my recomposed and duplicated remnants, squirming to reclaim their reality. See me run. This being is mine, however mutated and displaced, and I will do what I want with me, terms of service be damned.

There are ways out of genAI hell, most of them boringly obvious. The need for an omni-purposeful corpus of “training” data creates opportunities for solidarity across professions, to a degree I haven’t experienced before. I’ve felt empowered to write this piece in a more personal way because the same tools that are nibbling at my livelihood are also affecting developers at companies like King and ZeniMax Online Studios. The software’s function is to distil and paraphrase all of our contributions to the point that the source materials become irrelevant-seeming, blackboxed into oblivion. But we can push back, together, because in most cases the fuckers still need us to consent to their appropriations, which is why they routinely bury the tools for withholding it. We can demand that genAIs be properly regulated, in terms of both their “training” and wider impacts. We can demand that they become public utilities.

It’s not a concrete practical solution, next to joining a union and petitioning for proper controls, but I think we should also reclaim the idea and practice of a software generator from Big AI. I think generators have a capacity for enchantment that is both particular to computers and continuous with older, pre-digital artforms such as dice and decks of cards. You see this enchantment in my gloomy mystical characterisations above. I think it needs to be liberated from the corporations who are now using genAI to wreck workplaces and culture.

Generative AI’s rapacious archival methods are an excuse for a little wander through certain works of literature. While researching this piece, I stumbled on Helicone, an open-source genAI debugging program. In Ancient Greek legend, the Helicon was a river that retreated underground after being polluted by the blood of the bard Orpheus, after he was ripped to pieces by the Maenads, intoxicated followers of the god of festivity and frenzy. It re-emerged from the earth cleansed of gore and bearing a different name – another macabre analogy for the dissections and transmutations of generative AI, but perhaps if we follow the river, it might lead us to the sea.

The Helicon also resurfaces in Seamus Heaney’s poem “Personal Helicon”, a series of boyish memories about peering into sunken waters. Some watering wells, Heaney writes, “gave back your own call / with a clean new music in it. And one / was scaresome, for there, out of ferns and tall / foxgloves, a rat slapped across my reflection.” In Heaney’s accounting, the rules of which poems are composed are themselves a kind of well, akin to a primordial generator: a synaesthesiac, hallucinatory structure that glimmers and resounds, captures and delights and alarms the person peering into it. “I rhyme / to see myself, to set the darkness echoing.”

The poem’s own rhyme scheme consists of softly warped alternating couplets, an everyday poetic form that is as old as spoken English. While pursuing his own childhood reflections, Heaney offers this rhyming tradition to us as a structure in which we might see ourselves reinvented, but which also cultivates some healthy curiosity and dread about how this edifice of representation operates – what it leaves unseen.

To my knowledge, Heaney never did any literary work with computers, but I thought of “Personal Helicon” the first time I read this blog post about the 1989 platformer Monster Party by game developer Stephen “thecatamites” Gilmurphy, in which he suggests that interacting with a video game is like dropping stones down a well. “There might be a splash, or no splash, or a pause and then a splash, or it might cause somebody to climb out of the well and beat you up,” Gilmurphy writes.

However plausible, each outcome of an interaction is a different kind of “elaborate fake” on the part of intangible computer code, with no guarantee of an intuitive pattern. This makes the act of completing smaller tasks a joyfully monotonous exercise in checking that the world has some permanence – much as the repetitions of a rhyme scheme, even a tin-eared one, grip the darkness of a poem together, and much as “prompting” a generative AI is strangely compulsive. “There’s a pleasure which is also fear,” Gilmurphy continues. “These things offer an expanded field of capabilities in some way but those capabilities are also virtual and unreal, they can only be made to feel real by giving them a constant procession of invented obstacles to knock against.”

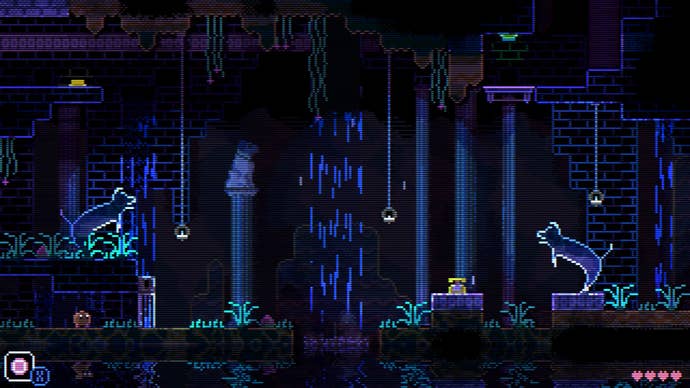

Games that involve procedural generation – broadly defined, the generation of materials according to procedures meticulously devised by the developers, rather than being abstracted from a dataset by a “learning” model – at once magnify and, perhaps, commodify this pleasure and fear, because procgen trades more deliberately on the premise of a hadal unreality. Keep lobbing rocks down the well and eventually, the abyss will foam up and burgeon with aberrations. While procgen has been a source of workplace efficiencies, as when flash-growing a forest using SpeedTree, that capacity for surprise is a huge part of the charm. There is, moreover, a sense of proportion and a rhetoric of accountability in the realm of procgen you don’t get from later all-consuming, all-purpose generative AIs. However comprehensive their source materials and outputs, procedural generators are not framed as autonomous beings that can stand in for the work of thousands.

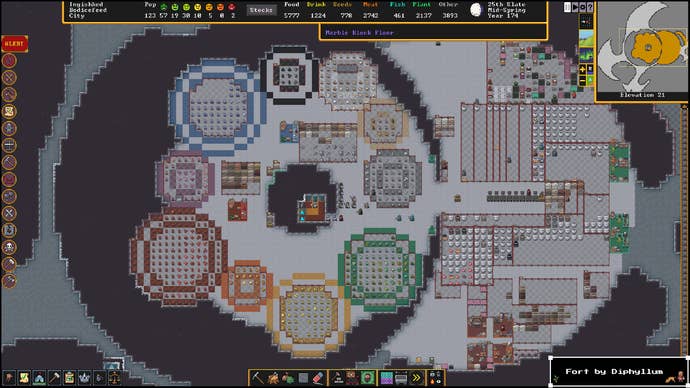

Some great procgen games mythologise their own drift towards incoherence. Minecraft, the most famous procgen enterprise of all, has retrospectively told stories about the breakdown of its own generator in the shape of “the Far Lands” – a series of legends about that astounding, porous nightmare frontier that springs up in older builds, when you travel sufficiently far from spawn. Dwarf Fortress is a story about the instability of generated worlds – the tendency for the darkness below to overwhelm the representation. The deeper you dig, the more likely your colony will be swamped by tectonic white noise and creatures whose generated descriptions are all but impossible to picture.

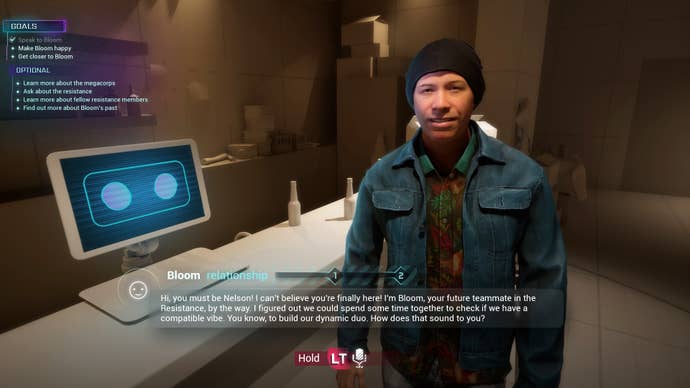

There is delight in provoking such generators, in striking the dark and being caught out, that is encapsulated by Nix Umbra, the randomised occult exploration game pictured in this article’s header. I create occult generators of a sort myself – little scruffy oracles of text fragments I’ve composed, that are dealt out according to certain rules to produce vocalisations, apparitions. You cut the deck and a planet speaks. I find these generators useful because they free me from some of the neurotic self-loathing I’ve described above, by dispersing my old writing into a system of relations. I toss my words into the well and it separates and lifts them into constellations I hadn’t quite thought of, a clean new music that jolts and soothes and restores me.

Procedural generators are at once alternatives and precursors for today’s mythologisation of generative AI as a “copilot” or, as with Google’s Gemini, a subordinate twin. The horror of Gemini finds a face in Minecraft’s Herobrine, mythical dead brother of the game’s original creator, Markus Persson: a glare-eyed double of default protagonist Steve who supposedly lurks within the wayward code, deforming the geography and stalking the player.

If he now resembles a malevolent genAI puppet, however, it should be emphasised that Herobrine is a communal production, like Minecraft at large. He is a folk legend, never officially present in the game, a rumour gleefully sown and solidified by modders and fan artists and cosplayers, with the exasperated encouragement of the game’s developers. He’s the subject of a thousand creepypastas, repeatedly “removed” by older Minecraft updates in the manner of a parent opening a closet door to show the child there is no monster, then closing it again.

Minecraft is now the property of Microsoft, who have said that they and Mojang “currently” have no plans to make use of generative AI in Minecraft’s development. Given Microsoft’s apocalyptic obsession with generative AI, it’s surely just a matter of time. Minecraft has already been piped through a third-party AI model, Oasis, which generates a video based on patterns derived from many hours of game footage. If Oasis is ever “trained” on enough Minecraft material, as per the Borg-style assimilatory objectives of the wider genAI project, Herobrine will surely materialise within this simulation. He will appear there not as a whimsical fan conspiracy but a creature alienated from his own history, a white face hovering over the bottom of a pool of appropriations and regurgitations. As Heaney might say, a rat slops across our reflection.